Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Labuanbajo-Flores

A little town inhabited by fishermen, lies at the extreme western part of Flores Island. The town serves as a jumping off point for the trip to Komodo Island. It is a beautiful area for water skiing, wind surfing, fishing and many other marine activities.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Watublapi: Weaving life from cultural heritage

Watublapi: Weaving life from cultural heritage

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Sun, 10/08/2006 10:06 AM

Filomena Reiss, Contributor, Watublapi, Flores

""Oh, helelarak! Oh, helelarak!"" Welcome, welcome! As visitors walk toward the village of Watublapi on Flores island, they are greeted by the colorful spectacle of traditionally dressed women singing and dancing, welcoming guests to their village.

Their words of greeting mean friendship, loyalty and respect for customs. Visitors are blessed by the village elder with a sprinkle of holy water, and a selendang (shawl) is placed around a lucky guest. The show is just beginning.

Watublapi is derived from watu (stone) and blapi (sitting), and thus means ""sitting together"". The village is situated in the hills about a 45-minute drive northeast from the capital Maumere.

The drive is spectacular. Due to the active volcanoes scattered in different parts of the island, the land is extremely fertile and the land is thickly covered with all types of plants and trees: coconut, clove, cashew nuts, cacao and coffee. As visitors approach Watublapi, their eyes are immediately drawn to the colorful woven sarongs drying on clothes lines.

All the men and women in the welcome party are members of the Sanggar Bliran Sina cooperative, founded 21 years ago by Romano Rewo, a native of Watublapi.

Romano had traveled to many different hotels trying to sell hand-woven textiles made by his family, but he thought there must a better way to sell them; so he decided to form this organization. Another aim of Sanggar Bliran Sina is to revive and preserve ancient dyeing techniques, using natural dyes.

Following Romano's death in 1990, his enthusiastic son Daniel David took over Sanggar, which now consists of 55 active members of not only weavers, but also dancers and musicians.

The villagers' performance includes a selection of culturally significant dances and songs. The heartfelt singing and exuberant dancing is quite infectious, and visitors will soon be tapping their toes to the music.

The opening dance, Roa Mu'u, demonstrates the bonding of two families in a traditional marriage ceremony. The bride's family prepares the sacred adat (customary) sarong while the groom's family must bring an elephant tusk.

The sarong must bear an ancient motif called werak or wiriwanan, which symbolize fertility. These elephant tusk motifs existed before the arrival of Christianity to Flores, as trade goods to eastern Indonesia at the peak of the spice trade, and are a symbol of male fertility.

Roa Mu'u is the cutting of a banana tree, which represents overcoming the hardships that the new couple may encounter during their married life. Banana trees are known to grow back, even when it is cut down repeatedly.

The Togo dance and song depicts the communal threshing of harvested rice, using their feet to separate the rice seeds from the straw. Traditional prayers and poems are sung to the rice goddess. According to local beliefs, rice originally derived from the blood of a girl named Ina Nalu Pare. Singing songs dedicated to the rice goddess ensures that her spirit will stay close to the paddies, guaranteeing both good crops and protection from negative forces.

Included in the cultural program is a demonstration of producing handmade textiles -- from cleaning the cotton, spinning, tying (ikat), coloring with plant dyes and weaving the final textile, called tenunan.

There are two types of yarn used in weaving textiles. Homespun yarn is very time-consuming to make and uses cotton that is grown in weavers' gardens. Commercial yarn is bought at the market, ready to be dyed. This yarn is produced in Java and is sold at markets all over Flores.

""Tying"", or mengikat, refers to tying the motifs and designs on to the prepared yarn, which prevents the dyes from spreading into the tied part creating the motifs. The yarn is tied with strips made of leaves from the lontar palm or young coconut leaves, called gebang.

The dyeing process is the most tedious, especially in preparing natural dyes from plants. Dyeing the yarn takes at least three to four days, over which the yarns are dipped and soaked in the prepared dyes several times until the desired color is achieved by the weaver.

Indigo plants are harvested in the lowlands of Flores, and are valued for the deep blue shade they produce.

For the earthy brown shade, the entire root system of the mengkudu (morinda) tree are dug up, but only the bark of the root is used. This is pounded and mixed with the powdered bark of the loba tree. If the resulting reddish color is not satisfactory, three more types of tree bark are boiled and the yarns are soaked again in this dye.

Turmeric is pounded with the bark of the mango tree to obtain a yellow dye.

A recently introduced color is green, which is produced using the leaves of the mango tree. Because these leaves are very strong and difficult to crush, this color is the most difficult to produce.

Papaya and cassava leaves are also used to make green dyes, and are preferred by some weavers. The weavers are very resourceful and always looking for different varieties of plants, experimenting with the color intensity the plants produce as dyes.

It takes three to four weeks to make a small selendang from a commercial yarn using natural dyes, and three months if the yarn is handspun.

Men also play an important role in the process of making textiles, particularly in harvesting plant material for dyes. Digging the roots of the mengkudu tree is very strenuous, while sacks and sacks of indigo plants are harvested from the lowlands to make blue dyes. Other plant materials are found in the forest, and the men are usually given this task.

They also help pound most of the plant materials, and cooking the materials into a dye is also now part of the men's work -- especially when the women, often the men's wives, are busy weaving.

The cultural program concludes with a viewing of these labor-intensive, finished textiles. This is when the weavers are hoping -- perhaps anxiously -- that one of their textiles would be purchased, or at least appreciated, by visitors.

Since the founding of Sanggar Bliran Singa, the local economy has improved tremendously. One weaver commented that since joining Sanggar, she could send her children to school and she always had a stock of rice in the kitchen.

The cooperative has encouraged the hardworking people of Watublapi to retain their heritage through weaving while establishing an economic gateway in selling their woven products.

A trip to the village is a wonderful experience of seeing a cultural heritage not only being maintained, but also enhanced further toward the betterment of villagers' lives.

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Sun, 10/08/2006 10:06 AM

Filomena Reiss, Contributor, Watublapi, Flores

""Oh, helelarak! Oh, helelarak!"" Welcome, welcome! As visitors walk toward the village of Watublapi on Flores island, they are greeted by the colorful spectacle of traditionally dressed women singing and dancing, welcoming guests to their village.

Their words of greeting mean friendship, loyalty and respect for customs. Visitors are blessed by the village elder with a sprinkle of holy water, and a selendang (shawl) is placed around a lucky guest. The show is just beginning.

Watublapi is derived from watu (stone) and blapi (sitting), and thus means ""sitting together"". The village is situated in the hills about a 45-minute drive northeast from the capital Maumere.

The drive is spectacular. Due to the active volcanoes scattered in different parts of the island, the land is extremely fertile and the land is thickly covered with all types of plants and trees: coconut, clove, cashew nuts, cacao and coffee. As visitors approach Watublapi, their eyes are immediately drawn to the colorful woven sarongs drying on clothes lines.

All the men and women in the welcome party are members of the Sanggar Bliran Sina cooperative, founded 21 years ago by Romano Rewo, a native of Watublapi.

Romano had traveled to many different hotels trying to sell hand-woven textiles made by his family, but he thought there must a better way to sell them; so he decided to form this organization. Another aim of Sanggar Bliran Sina is to revive and preserve ancient dyeing techniques, using natural dyes.

Following Romano's death in 1990, his enthusiastic son Daniel David took over Sanggar, which now consists of 55 active members of not only weavers, but also dancers and musicians.

The villagers' performance includes a selection of culturally significant dances and songs. The heartfelt singing and exuberant dancing is quite infectious, and visitors will soon be tapping their toes to the music.

The opening dance, Roa Mu'u, demonstrates the bonding of two families in a traditional marriage ceremony. The bride's family prepares the sacred adat (customary) sarong while the groom's family must bring an elephant tusk.

The sarong must bear an ancient motif called werak or wiriwanan, which symbolize fertility. These elephant tusk motifs existed before the arrival of Christianity to Flores, as trade goods to eastern Indonesia at the peak of the spice trade, and are a symbol of male fertility.

Roa Mu'u is the cutting of a banana tree, which represents overcoming the hardships that the new couple may encounter during their married life. Banana trees are known to grow back, even when it is cut down repeatedly.

The Togo dance and song depicts the communal threshing of harvested rice, using their feet to separate the rice seeds from the straw. Traditional prayers and poems are sung to the rice goddess. According to local beliefs, rice originally derived from the blood of a girl named Ina Nalu Pare. Singing songs dedicated to the rice goddess ensures that her spirit will stay close to the paddies, guaranteeing both good crops and protection from negative forces.

Included in the cultural program is a demonstration of producing handmade textiles -- from cleaning the cotton, spinning, tying (ikat), coloring with plant dyes and weaving the final textile, called tenunan.

There are two types of yarn used in weaving textiles. Homespun yarn is very time-consuming to make and uses cotton that is grown in weavers' gardens. Commercial yarn is bought at the market, ready to be dyed. This yarn is produced in Java and is sold at markets all over Flores.

""Tying"", or mengikat, refers to tying the motifs and designs on to the prepared yarn, which prevents the dyes from spreading into the tied part creating the motifs. The yarn is tied with strips made of leaves from the lontar palm or young coconut leaves, called gebang.

The dyeing process is the most tedious, especially in preparing natural dyes from plants. Dyeing the yarn takes at least three to four days, over which the yarns are dipped and soaked in the prepared dyes several times until the desired color is achieved by the weaver.

Indigo plants are harvested in the lowlands of Flores, and are valued for the deep blue shade they produce.

For the earthy brown shade, the entire root system of the mengkudu (morinda) tree are dug up, but only the bark of the root is used. This is pounded and mixed with the powdered bark of the loba tree. If the resulting reddish color is not satisfactory, three more types of tree bark are boiled and the yarns are soaked again in this dye.

Turmeric is pounded with the bark of the mango tree to obtain a yellow dye.

A recently introduced color is green, which is produced using the leaves of the mango tree. Because these leaves are very strong and difficult to crush, this color is the most difficult to produce.

Papaya and cassava leaves are also used to make green dyes, and are preferred by some weavers. The weavers are very resourceful and always looking for different varieties of plants, experimenting with the color intensity the plants produce as dyes.

It takes three to four weeks to make a small selendang from a commercial yarn using natural dyes, and three months if the yarn is handspun.

Men also play an important role in the process of making textiles, particularly in harvesting plant material for dyes. Digging the roots of the mengkudu tree is very strenuous, while sacks and sacks of indigo plants are harvested from the lowlands to make blue dyes. Other plant materials are found in the forest, and the men are usually given this task.

They also help pound most of the plant materials, and cooking the materials into a dye is also now part of the men's work -- especially when the women, often the men's wives, are busy weaving.

The cultural program concludes with a viewing of these labor-intensive, finished textiles. This is when the weavers are hoping -- perhaps anxiously -- that one of their textiles would be purchased, or at least appreciated, by visitors.

Since the founding of Sanggar Bliran Singa, the local economy has improved tremendously. One weaver commented that since joining Sanggar, she could send her children to school and she always had a stock of rice in the kitchen.

The cooperative has encouraged the hardworking people of Watublapi to retain their heritage through weaving while establishing an economic gateway in selling their woven products.

A trip to the village is a wonderful experience of seeing a cultural heritage not only being maintained, but also enhanced further toward the betterment of villagers' lives.

Flores: Hidden flower of the East

Flores: Hidden flower of the East

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Sun, 09/04/2005

Christina Schott, Contributor, Jakarta

Flores. For years we wanted to go Cabo da Flores (Cape of Flowers), as the Portuguese called the island in today's East Nusa Tenggara when they first arrived in 1512. Whether they chose this name because of the beautiful vegetation or because of the colorful underwater gardens is not clear. Both are overwhelming in the right season; just after the rain is over, when the mud has dried but the dust has not yet risen.

That was the moment, as we sat on a flight to Maumere, we had the idea to roll east to west along the Trans-Flores highway. From the air, we got the first impression of the breathtaking landscape waiting for us: Flores, 375 kilometers long but extremely slim, presents dramatic mountain scenery up to 2,400 meters above sea level and 14 active volcanoes. And even from high up we could see the clear turquoise water around the northern coast, with its coral reefs that promised to fulfill every diver's dream.

As an important junction, Maumere is a good place to start in, although the town was mostly destroyed by a devastating tsunami in 1992. Since there was not even a fraction of the international attention last year's tsunami drew, the thousands of victims had to rebuild their homes with few donors in a rather unattractive way. However, some quiet bungalow resorts on the way to Larantuka -- once the headquarters of the Portuguese Dominicans -- provide pristine, white sandy beaches and access to snorkeling and diving spots.

Very soon, however, we learned that transport on Flores not only needs time but it also has its price: Either you pay in U.S. dollars for a private car or you bump your body around chicken cages and other loads piled up in the middle of a public bus. We chose the second option, hoping to get some travel originality. We got it. With three goats and a pig screaming on top of our heads and the finest selection of East Nusa Tenggara hits of the Eighties. All at full volume, of course.

We also understood quickly, why every passenger on the bus was greeted with the distribution of plastic bags. The ""Trans-Flores-Highway"" is, indeed, the biggest road on the island but that doesn't mean much, since it is often the only asphalted one. It is an ever-winding mountain pass road that hardly provides enough space for two buses passing each other, let alone the potholes. ""Nothing compared to 40 years ago,"" reassured a retired missionary who had first arrived on Flores in the 1960s. ""At that time, the trip to Ende took us a whole day on dusty earth.""

Nevertheless, the stomach- and buttock-torturing journey was worth every kilometer for its gorgeous panoramic views. We needed four hours to our first stop at Moni, the gateway for a visit to Mount Kelimutu, whose three-colored crater lakes are one of Flores most famous tourist attractions. Early in the morning, two hired motorbikes took us to the freezing dark on top of the volcano. Every story the villagers told us the night before about ghosts and other mysteries suddenly seemed very real.

From the parking still half-an-hour-climb through the fog, we reached the platform on the top just in time to imagine the sunrise behind the impenetrable clouds. Thanks to our sarongs and thermos bottle with hot tea we could stand the cold a little longer than the disappointed Dutch travel group that arrived with us so that we were on our own to witness the sun breaking through and turning the three dark water holes around us into the bubbling crater lakes we were hoping for. Because of unexplored chemical reactions the color of the lakes have changed several times in the last decades, leaving them now in a shimmering black, sparkling turquoise and rusty dark brown. The souls of the dead are said to live here and we could imagine them dancing in the steam rising up the steep slopes.

After a two-hour bus ride and a 15 degree Celsius difference in temperature we reached Ende. The capital of Flores doesn't offer much as a tourist attraction except a dirty harbor and one of the island's three public Internet cafes; the others are in Maumere and Ruteng. It is also a good place to buy famous ikat (traditional weaving) made all over the island and to prepare oneself for the freezing nights at the next stop in the mountains: Bajawa.

The main town of the Ngada region is -- beside Labuanbajo -- probably the best-prepared for travelers. Everything is organized by local guides and the bemo (three-wheeled motor taxi) mafia, and even their tour prizes are fixed. But you need them: We probably would never have found our way to the traditional villages of the Ngada people alone. A few kilometers can become a long winding way through an unknown forest. Another problem is the language: not all of the indigenous people speak Indonesian. As different as the climate on Flores is, as different are the peoples, their features and their languages.

The Ngada normally live in matriarchal communities with strict sacred rules. Although they were converted to Catholicism -- the graves in front of their towering wooden houses show crosses -- they still follow many animist traditions. Among the crosses, there are megalithic altars and a lot of other symbols like the ngadhu and bhaga, reminding us of the female and male ancestors of every clan living in the village. On top of these open graveyards play the children along with cats and pigs, as the mothers weave the traditional black-and-white ikat. But behind their brown stained smiles -- what the sirih (betel) addiction left of their teeth -- lurk symbols of modernity; Coca-Cola boxes in the back of their houses.

After a soothing bath in the nearby hot springs of Soa, we are ready for our last bone-shaking bus trip next morning. It starts with an impressing tour around Mount Inerie, and offers direct views to the sea from the top of the peaks before reaching the Manggarai capital Ruteng. From there it is still another four-hour-drive to Labuanbajo. This bustling harbor town is mainly inhabited by Muslim immigrants from Sulawesi and is the starting point for all kinds of boat trips to the innumerable islands between Flores and Sumbawa -- before all go to Komodo National Park.

We need a break after all the bumpy streets and the shouting bus drivers. So we head straight away to Seraya, one of small islands around Labuanbajo; islands which are rented from the government by hotels. Seraya Kecil looks like it was arranged for a travel advertisement: surrounded by white sandy beaches, transparent water and beautiful coral reefs. The island accommodates a small fishing village and -- at the other end -- a dozen simple but clean bamboo bungalows. The only permanent inhabitants there are a couple of deer, a family of dogs and a herd of goats. The rest is all yours.

How to get there:

Flights from Denpasar starting from Rp 500,000 by Merpati or Pelita (to Ende, Maumere, Labuanbajo) and GT Air (to Labuanbajo). PELNI ships go on different routes from Surabaya to Ende, Maumere and Labuanbajo. The trip by public bus and ferry takes around three days from Bali.

Where to stay:

Maumere: Sea World Club, Waiara (13 km from Maumere), Phone: +62-382-21570, www.sea-world-club.com

Ende: Hotel Ikhlas, Jl. Ahmad Yani, Phone: +62-381-21695. Upscale traveler hotel, clean and organized.

Labuanbajo: Those who don't want to stay in the busy immigrant town, should take the Gardena boat to Seraya island and find Robinson's paradise; Seraya Island Bungalows, c/o Gardena Hotel, Labuanbajo. Phone: +62-385-41258, www.serayaisland.com

Transport:

Those who don't want to rely on the uncomfortable public transport or see places off the beaten track, should arrange a car and a guide. Warmly recommended: Leonardus Nyoman, experienced guide, speaks English and German, phone: +62-812-366 2110, Email: leonardus_nym@yahoo.com

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Sun, 09/04/2005

Christina Schott, Contributor, Jakarta

Flores. For years we wanted to go Cabo da Flores (Cape of Flowers), as the Portuguese called the island in today's East Nusa Tenggara when they first arrived in 1512. Whether they chose this name because of the beautiful vegetation or because of the colorful underwater gardens is not clear. Both are overwhelming in the right season; just after the rain is over, when the mud has dried but the dust has not yet risen.

That was the moment, as we sat on a flight to Maumere, we had the idea to roll east to west along the Trans-Flores highway. From the air, we got the first impression of the breathtaking landscape waiting for us: Flores, 375 kilometers long but extremely slim, presents dramatic mountain scenery up to 2,400 meters above sea level and 14 active volcanoes. And even from high up we could see the clear turquoise water around the northern coast, with its coral reefs that promised to fulfill every diver's dream.

As an important junction, Maumere is a good place to start in, although the town was mostly destroyed by a devastating tsunami in 1992. Since there was not even a fraction of the international attention last year's tsunami drew, the thousands of victims had to rebuild their homes with few donors in a rather unattractive way. However, some quiet bungalow resorts on the way to Larantuka -- once the headquarters of the Portuguese Dominicans -- provide pristine, white sandy beaches and access to snorkeling and diving spots.

Very soon, however, we learned that transport on Flores not only needs time but it also has its price: Either you pay in U.S. dollars for a private car or you bump your body around chicken cages and other loads piled up in the middle of a public bus. We chose the second option, hoping to get some travel originality. We got it. With three goats and a pig screaming on top of our heads and the finest selection of East Nusa Tenggara hits of the Eighties. All at full volume, of course.

We also understood quickly, why every passenger on the bus was greeted with the distribution of plastic bags. The ""Trans-Flores-Highway"" is, indeed, the biggest road on the island but that doesn't mean much, since it is often the only asphalted one. It is an ever-winding mountain pass road that hardly provides enough space for two buses passing each other, let alone the potholes. ""Nothing compared to 40 years ago,"" reassured a retired missionary who had first arrived on Flores in the 1960s. ""At that time, the trip to Ende took us a whole day on dusty earth.""

Nevertheless, the stomach- and buttock-torturing journey was worth every kilometer for its gorgeous panoramic views. We needed four hours to our first stop at Moni, the gateway for a visit to Mount Kelimutu, whose three-colored crater lakes are one of Flores most famous tourist attractions. Early in the morning, two hired motorbikes took us to the freezing dark on top of the volcano. Every story the villagers told us the night before about ghosts and other mysteries suddenly seemed very real.

From the parking still half-an-hour-climb through the fog, we reached the platform on the top just in time to imagine the sunrise behind the impenetrable clouds. Thanks to our sarongs and thermos bottle with hot tea we could stand the cold a little longer than the disappointed Dutch travel group that arrived with us so that we were on our own to witness the sun breaking through and turning the three dark water holes around us into the bubbling crater lakes we were hoping for. Because of unexplored chemical reactions the color of the lakes have changed several times in the last decades, leaving them now in a shimmering black, sparkling turquoise and rusty dark brown. The souls of the dead are said to live here and we could imagine them dancing in the steam rising up the steep slopes.

After a two-hour bus ride and a 15 degree Celsius difference in temperature we reached Ende. The capital of Flores doesn't offer much as a tourist attraction except a dirty harbor and one of the island's three public Internet cafes; the others are in Maumere and Ruteng. It is also a good place to buy famous ikat (traditional weaving) made all over the island and to prepare oneself for the freezing nights at the next stop in the mountains: Bajawa.

The main town of the Ngada region is -- beside Labuanbajo -- probably the best-prepared for travelers. Everything is organized by local guides and the bemo (three-wheeled motor taxi) mafia, and even their tour prizes are fixed. But you need them: We probably would never have found our way to the traditional villages of the Ngada people alone. A few kilometers can become a long winding way through an unknown forest. Another problem is the language: not all of the indigenous people speak Indonesian. As different as the climate on Flores is, as different are the peoples, their features and their languages.

The Ngada normally live in matriarchal communities with strict sacred rules. Although they were converted to Catholicism -- the graves in front of their towering wooden houses show crosses -- they still follow many animist traditions. Among the crosses, there are megalithic altars and a lot of other symbols like the ngadhu and bhaga, reminding us of the female and male ancestors of every clan living in the village. On top of these open graveyards play the children along with cats and pigs, as the mothers weave the traditional black-and-white ikat. But behind their brown stained smiles -- what the sirih (betel) addiction left of their teeth -- lurk symbols of modernity; Coca-Cola boxes in the back of their houses.

After a soothing bath in the nearby hot springs of Soa, we are ready for our last bone-shaking bus trip next morning. It starts with an impressing tour around Mount Inerie, and offers direct views to the sea from the top of the peaks before reaching the Manggarai capital Ruteng. From there it is still another four-hour-drive to Labuanbajo. This bustling harbor town is mainly inhabited by Muslim immigrants from Sulawesi and is the starting point for all kinds of boat trips to the innumerable islands between Flores and Sumbawa -- before all go to Komodo National Park.

We need a break after all the bumpy streets and the shouting bus drivers. So we head straight away to Seraya, one of small islands around Labuanbajo; islands which are rented from the government by hotels. Seraya Kecil looks like it was arranged for a travel advertisement: surrounded by white sandy beaches, transparent water and beautiful coral reefs. The island accommodates a small fishing village and -- at the other end -- a dozen simple but clean bamboo bungalows. The only permanent inhabitants there are a couple of deer, a family of dogs and a herd of goats. The rest is all yours.

How to get there:

Flights from Denpasar starting from Rp 500,000 by Merpati or Pelita (to Ende, Maumere, Labuanbajo) and GT Air (to Labuanbajo). PELNI ships go on different routes from Surabaya to Ende, Maumere and Labuanbajo. The trip by public bus and ferry takes around three days from Bali.

Where to stay:

Maumere: Sea World Club, Waiara (13 km from Maumere), Phone: +62-382-21570, www.sea-world-club.com

Ende: Hotel Ikhlas, Jl. Ahmad Yani, Phone: +62-381-21695. Upscale traveler hotel, clean and organized.

Labuanbajo: Those who don't want to stay in the busy immigrant town, should take the Gardena boat to Seraya island and find Robinson's paradise; Seraya Island Bungalows, c/o Gardena Hotel, Labuanbajo. Phone: +62-385-41258, www.serayaisland.com

Transport:

Those who don't want to rely on the uncomfortable public transport or see places off the beaten track, should arrange a car and a guide. Warmly recommended: Leonardus Nyoman, experienced guide, speaks English and German, phone: +62-812-366 2110, Email: leonardus_nym@yahoo.com

Monday, April 18, 2011

Toraja Land, Sulawesi Indonesia

Toraja Land, Sulawesi Indonesia

Tana Toraja is located in the Northern part of the South Sulawesi Province. Situated between Latimojong Mountain range and Mount Reute Kambola. The arible Toraja consists of three groups. The Eastern around lake Poso, Western Toraja living around the Palu river and Kalawi in Centre Sulawesi. Toraja Traditional House, Kete kesuThe Specific architecture of Torajan house has its own architecture form. Toraja house are shaped like a bout and the two ends are shaped like the bow. Torajan house is a compound buildings consist of traditional houses (Tongkonan) and rice storage buildings (Lumbung). The building are sculpted with ornaments of various shapes. The ornament is painted with traditional colour dominated with the black and red colour. All of them create the aesthetic value of the building of Torajan houses.

Demography

Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until quite recently Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughlyYoung women in Toraja Land 60% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a Tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

The Toraja are divided up geographically into different groups, the most important of which are the Mamasa, who are centred around the isolated Kalumpang valley, and the Sa'dan of the southern Toraja lands. There have never been any strong, lasting political groupings within the Toraja. The Sa'dan area, with its market towns of Makale and Rantepao, is known as Tana Toraja. Good roads now reach Tana Toraja from Makassar or formerly known as Ujung Panjang, the capital of Sulawesi, bringing a large seasonal influx of foreign tourists who, while injecting money into the local economy, have not yet had much lasting affect on local people's lives.

Village Pattern

In former times, Toraja villages were sited strategically on hilltops and fortified to such an extent that sometimes access was only possible through tunnels bored through rock. This was all part of the then common Indonesian custom of hStone grave in Toraja landead-hunting and inter-village raids. The Dutch pacified the Toraja and forced them to leave the hills and to build their villages in the valleys, and they also introduced wet-rice cultivation. The Toraja abandoned their traditional slashand-burn agricultural policy and now live by rice-farming, and raising pigs and beautiful buffalo.

The Toraja are a proto-Malay people whose origins lie in mainland South-East Asia (possibly Cambodia). Toraja legends claim that they arrived from the north by sea. Caught in a violent storm, their boats were so damaged as to be unseaworthy, so instead they used them as roofs for their new homes. The Tongkonan, with their boat-shaped roofs, always face towards the north.

Style & Construction

Tongkonan are built on wooden piles. They have saddleback roofs whose gables sweep up at an even more exaggerated pitch than those of the Toba Barak. Traditionally, the roof is constructed with layered bamboo, Rice terrace in Torajaand the wooden structure of the house assembled in tongue-and-groove fashion without nails. Nowadays, of course, zinc roofs and nails are used increasingly.

The construction of a traditional rumah adat is time-consuming and complex, and requires the employment of skilled craftsmen. First of all, seasoned timber is collected, then a shed of bamboo scaffolding with a bamboo shingle roof is erected. Here, components of the house are prefabricated, though the final assembly will take place at the actual site. Almost invariably now, Tongkonan are raised on vertical piles rather than on a substructure of the log-cabin type, so al the wooden piles are shaped and mortises cut in them to take the horizontal tie beams. The piles are notched at the top to accommodate the longitudinal and transverse beams of the upper structure. The substucture is then assembled at the final site. Next, the transverse beams are fitted into the piles, then notched and the longitudinal beams set into them, and the grooved uprights that will form the frame for the side walls are pegged in place. Thin side panels are cut to the dimensions decided on by the woodcarver who is going to decorate them, and slotted in, The two outermost uprights of each transverse wall pass through the upper horizontal wall beam and, being forked at the upper end, carry the parallel horizontal beams that support the rafters. A narrow hardwood post, also forked at the top and set into the central longitudinal floor beam, runs up each transverse wall, is anchored to the upper wall beam and carries the ridge purlin. The rafters are laid over the ridge purlin, whose extended ends rest on the triangular overhanging gables. An upper ridge pole is then laid in the crosses formed by the rafters, and the ridge pole and ridge purlin lashed together with rattan.

To obtain the increasingly curved roof so popular with the Toraja, the ends of the upper ridge pole must be slotted through the centres of short vertical hanging spars, whose upper halves support the first of the upwardly angled beams at the front and rear of the house, which in turn slots through the centre of further short vertical hanging spars that carry the second upwardly angled beam. The sections of the ridge pole projecting beyond the ridge purlin are supported front and back by a freestanding pole. Transverse ties pass through both the hanging spars and the freestanding posts to support the rafters of the projecting roof. Before the roof is fitted, stones are placed under the piles. The roof is made of bamboo staves bound together with rattan and assembled transversely in layers over an under-roof of bamboo poles, which are tied longitudinally to the rafters. Flooring is of wooden boards laid over thin hardwood joists.

A new Tongkonan at Pa'tengko, just outside Makale, took eight men three months to build, and six men one month to carve and paint the outside wall panels. There is no carving inside recently built Toraja houses, but on occasion timbers from old houses are reused in the construction of new ones. In Bintu Lepang, in the Solo district of Tana Toraja, there is a house which dates from about 1950 that was made out of beams and posts from three older houses. Here old carved exterior beams were incorporated into the new interior. This Tongkonan was notorious for housing an unburied corpse from 1964 until 1992, as a result of a dispute between the dead woman's adopted children. The body was soaked in coffee to preserve it and wrapped in over fifty of her textiles to smother the smell and to stop the heirs from squabbling over the them. The government finally had to order the funeral to take place.

Social Organization

Toraja society is extremely hierarchical, comprising nobility, commoners and a lower class who were formerly slaves. Villagers are only permitte to decor their house with the symbols and motifs appropriate to their social station. The gables and the wooden wall panels are incised with geometric, spiralling designs and motifs such as buffalo heads and cockerels painted in red, white, yellow and black, the colours that represent the various festivals of Aluk To Dolo ('the Way of the Ancestors'), the indigenous Torala religion. Black symbolizes death and darkness; yellow, God's blessing and power; white, the colour of flesh and bone, means purity; and red, the colour of blood, symbolizes human life. The pigments used were of readily available materials, soot for black, lime for white and coloured earth for red and yellow; tuak (palm wine) was used to strengthen the colours. The artists who decorated the house were traditionally paid with buffalo. The majority of the carvings on Toraja houses and granaries signify prosperity and fertility, and the motifs used are those important to the owner's family. Circular motifs represent the sun, the symbol of power, a golden keris (knife) symbolizes wealth and buffalo heads stand for prosperity and ritual sacrifice. Many of the designs are associated with water, which in itself symbolizes life, fertility and prolific rice fields. Tadpoles and water-weeds, both of which breed rapidly, represent hopes for many children.

Many of the motifs that adorn the houses and granaries of the Toraja are identical to those found on the bronze kettle drums of the Dong-Son. Others, such as the square cross motif, are thought to have Hindu-Buddhist origins or to have been copied from Indian trade cloths. The cross is used by the Christian Toraja as a decorative design emblematic of their faith. On the front wall of the most important houses of origin is mounted a realistically carved wooden buffalo head, adorned with actual horns. This emblem may only be added to the house after one of the most important funeral rites has been celebrated.

Village layout varies according to size. As a general rule, in the larger settlements of Tana Toraja the houses are arranged in a row, side by side, with their front gables facing north. Each house stands opposite its own rice barn, and together these form a complementary row parallel to the houses. Roofs are aligned on a north-south axis. Houses of the Mamasa Toraja are not orientated in this way but follow the direction of the river, and their rice barns are set at right-angles to the houses. The major agricultural ceremonies of the Toraja year are celebrated in the area between the houses and the barns.

To the Toraja, the Tongkonan is more than just a structure. The symbol of family identity and tradition, representing all the descendants of a founding ancestor, it is the focus of ritual life. It forms the most important nexus within the web of kindship. Torajans may have difficulty defining their exact relationship to distant kind, but can always name the natal houses of parents, grandparents and sometimes distant ancestors, for they consider themselves to be related through these houses. Descent amongst the Toraja is traced bilaterally - that is, through both the male and female line. People therefore belong to more than one house. Membership of these houses only requires the kinsman's active participation at times of ceremony, the division of an inheritance or when a house is rebuilt.

Although the Tongkonan has become identified by outsiders as being representative of all Toraja building, it is only the nobility and their descendants who can afford both the building of the houses themselves and the enormous ritual feasts associated with them. Noble Toraja can claim affiliation to a particular Tongkonan as descendants of the founding ancestor, through the male or female line. This association is periodically confirmed through contributions to the ceremonial feasts given by the Tongkonan household. Commoners customarily lived in smaller, simpler houses and acted as helpers at these communal feasts. Commoners trace their descent through their own houses of origin. These, although of simpler design and decoration, may still be known as Tongkonan.

Upon marriage, Toraja men will usually go to live with their wives. If they later divorce, the husband is the one who will leave, his ex-wife being left in possession of a house that he may have spent much time, energy and money on refurbishing. He is often compensated by being given the rice barn, which he dismantles and removes. The Tongkonan is never moved. One important reason for this is that a large number of placentae are buried to the east side of the house (east is associated with life in Tora'a mythology). The placentae, buried by the fathers of new-born children, are believed to call them back if in their adult life they ever journey a long way from home, so ensuring that they will always return to their house of origin.

As in so many places in modern Indonesia, the traditional house, with its cramped, dark, smoky interior, has lost its attraction for many Torala (although it still commands great ritual prestige). Many have opted for a ground-built, concrete, single-storey house in the contemporary Pan-Indonesian style, and some have adopted a wooden, pile-built Bu 's-type dwelling. Others who are more inclined towards tradition may add an extra storey and a saddleback roof; this provides more living space and room for furniture whilst retaining something of the prestige the Tongkonan affords its owner.

Tana Toraja is located in the Northern part of the South Sulawesi Province. Situated between Latimojong Mountain range and Mount Reute Kambola. The arible Toraja consists of three groups. The Eastern around lake Poso, Western Toraja living around the Palu river and Kalawi in Centre Sulawesi. Toraja Traditional House, Kete kesuThe Specific architecture of Torajan house has its own architecture form. Toraja house are shaped like a bout and the two ends are shaped like the bow. Torajan house is a compound buildings consist of traditional houses (Tongkonan) and rice storage buildings (Lumbung). The building are sculpted with ornaments of various shapes. The ornament is painted with traditional colour dominated with the black and red colour. All of them create the aesthetic value of the building of Torajan houses.

Demography

Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until quite recently Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughlyYoung women in Toraja Land 60% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a Tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

The Toraja are divided up geographically into different groups, the most important of which are the Mamasa, who are centred around the isolated Kalumpang valley, and the Sa'dan of the southern Toraja lands. There have never been any strong, lasting political groupings within the Toraja. The Sa'dan area, with its market towns of Makale and Rantepao, is known as Tana Toraja. Good roads now reach Tana Toraja from Makassar or formerly known as Ujung Panjang, the capital of Sulawesi, bringing a large seasonal influx of foreign tourists who, while injecting money into the local economy, have not yet had much lasting affect on local people's lives.

Village Pattern

In former times, Toraja villages were sited strategically on hilltops and fortified to such an extent that sometimes access was only possible through tunnels bored through rock. This was all part of the then common Indonesian custom of hStone grave in Toraja landead-hunting and inter-village raids. The Dutch pacified the Toraja and forced them to leave the hills and to build their villages in the valleys, and they also introduced wet-rice cultivation. The Toraja abandoned their traditional slashand-burn agricultural policy and now live by rice-farming, and raising pigs and beautiful buffalo.

The Toraja are a proto-Malay people whose origins lie in mainland South-East Asia (possibly Cambodia). Toraja legends claim that they arrived from the north by sea. Caught in a violent storm, their boats were so damaged as to be unseaworthy, so instead they used them as roofs for their new homes. The Tongkonan, with their boat-shaped roofs, always face towards the north.

Style & Construction

Tongkonan are built on wooden piles. They have saddleback roofs whose gables sweep up at an even more exaggerated pitch than those of the Toba Barak. Traditionally, the roof is constructed with layered bamboo, Rice terrace in Torajaand the wooden structure of the house assembled in tongue-and-groove fashion without nails. Nowadays, of course, zinc roofs and nails are used increasingly.

The construction of a traditional rumah adat is time-consuming and complex, and requires the employment of skilled craftsmen. First of all, seasoned timber is collected, then a shed of bamboo scaffolding with a bamboo shingle roof is erected. Here, components of the house are prefabricated, though the final assembly will take place at the actual site. Almost invariably now, Tongkonan are raised on vertical piles rather than on a substructure of the log-cabin type, so al the wooden piles are shaped and mortises cut in them to take the horizontal tie beams. The piles are notched at the top to accommodate the longitudinal and transverse beams of the upper structure. The substucture is then assembled at the final site. Next, the transverse beams are fitted into the piles, then notched and the longitudinal beams set into them, and the grooved uprights that will form the frame for the side walls are pegged in place. Thin side panels are cut to the dimensions decided on by the woodcarver who is going to decorate them, and slotted in, The two outermost uprights of each transverse wall pass through the upper horizontal wall beam and, being forked at the upper end, carry the parallel horizontal beams that support the rafters. A narrow hardwood post, also forked at the top and set into the central longitudinal floor beam, runs up each transverse wall, is anchored to the upper wall beam and carries the ridge purlin. The rafters are laid over the ridge purlin, whose extended ends rest on the triangular overhanging gables. An upper ridge pole is then laid in the crosses formed by the rafters, and the ridge pole and ridge purlin lashed together with rattan.

To obtain the increasingly curved roof so popular with the Toraja, the ends of the upper ridge pole must be slotted through the centres of short vertical hanging spars, whose upper halves support the first of the upwardly angled beams at the front and rear of the house, which in turn slots through the centre of further short vertical hanging spars that carry the second upwardly angled beam. The sections of the ridge pole projecting beyond the ridge purlin are supported front and back by a freestanding pole. Transverse ties pass through both the hanging spars and the freestanding posts to support the rafters of the projecting roof. Before the roof is fitted, stones are placed under the piles. The roof is made of bamboo staves bound together with rattan and assembled transversely in layers over an under-roof of bamboo poles, which are tied longitudinally to the rafters. Flooring is of wooden boards laid over thin hardwood joists.

A new Tongkonan at Pa'tengko, just outside Makale, took eight men three months to build, and six men one month to carve and paint the outside wall panels. There is no carving inside recently built Toraja houses, but on occasion timbers from old houses are reused in the construction of new ones. In Bintu Lepang, in the Solo district of Tana Toraja, there is a house which dates from about 1950 that was made out of beams and posts from three older houses. Here old carved exterior beams were incorporated into the new interior. This Tongkonan was notorious for housing an unburied corpse from 1964 until 1992, as a result of a dispute between the dead woman's adopted children. The body was soaked in coffee to preserve it and wrapped in over fifty of her textiles to smother the smell and to stop the heirs from squabbling over the them. The government finally had to order the funeral to take place.

Social Organization

Toraja society is extremely hierarchical, comprising nobility, commoners and a lower class who were formerly slaves. Villagers are only permitte to decor their house with the symbols and motifs appropriate to their social station. The gables and the wooden wall panels are incised with geometric, spiralling designs and motifs such as buffalo heads and cockerels painted in red, white, yellow and black, the colours that represent the various festivals of Aluk To Dolo ('the Way of the Ancestors'), the indigenous Torala religion. Black symbolizes death and darkness; yellow, God's blessing and power; white, the colour of flesh and bone, means purity; and red, the colour of blood, symbolizes human life. The pigments used were of readily available materials, soot for black, lime for white and coloured earth for red and yellow; tuak (palm wine) was used to strengthen the colours. The artists who decorated the house were traditionally paid with buffalo. The majority of the carvings on Toraja houses and granaries signify prosperity and fertility, and the motifs used are those important to the owner's family. Circular motifs represent the sun, the symbol of power, a golden keris (knife) symbolizes wealth and buffalo heads stand for prosperity and ritual sacrifice. Many of the designs are associated with water, which in itself symbolizes life, fertility and prolific rice fields. Tadpoles and water-weeds, both of which breed rapidly, represent hopes for many children.

Many of the motifs that adorn the houses and granaries of the Toraja are identical to those found on the bronze kettle drums of the Dong-Son. Others, such as the square cross motif, are thought to have Hindu-Buddhist origins or to have been copied from Indian trade cloths. The cross is used by the Christian Toraja as a decorative design emblematic of their faith. On the front wall of the most important houses of origin is mounted a realistically carved wooden buffalo head, adorned with actual horns. This emblem may only be added to the house after one of the most important funeral rites has been celebrated.

Village layout varies according to size. As a general rule, in the larger settlements of Tana Toraja the houses are arranged in a row, side by side, with their front gables facing north. Each house stands opposite its own rice barn, and together these form a complementary row parallel to the houses. Roofs are aligned on a north-south axis. Houses of the Mamasa Toraja are not orientated in this way but follow the direction of the river, and their rice barns are set at right-angles to the houses. The major agricultural ceremonies of the Toraja year are celebrated in the area between the houses and the barns.

To the Toraja, the Tongkonan is more than just a structure. The symbol of family identity and tradition, representing all the descendants of a founding ancestor, it is the focus of ritual life. It forms the most important nexus within the web of kindship. Torajans may have difficulty defining their exact relationship to distant kind, but can always name the natal houses of parents, grandparents and sometimes distant ancestors, for they consider themselves to be related through these houses. Descent amongst the Toraja is traced bilaterally - that is, through both the male and female line. People therefore belong to more than one house. Membership of these houses only requires the kinsman's active participation at times of ceremony, the division of an inheritance or when a house is rebuilt.

Although the Tongkonan has become identified by outsiders as being representative of all Toraja building, it is only the nobility and their descendants who can afford both the building of the houses themselves and the enormous ritual feasts associated with them. Noble Toraja can claim affiliation to a particular Tongkonan as descendants of the founding ancestor, through the male or female line. This association is periodically confirmed through contributions to the ceremonial feasts given by the Tongkonan household. Commoners customarily lived in smaller, simpler houses and acted as helpers at these communal feasts. Commoners trace their descent through their own houses of origin. These, although of simpler design and decoration, may still be known as Tongkonan.

Upon marriage, Toraja men will usually go to live with their wives. If they later divorce, the husband is the one who will leave, his ex-wife being left in possession of a house that he may have spent much time, energy and money on refurbishing. He is often compensated by being given the rice barn, which he dismantles and removes. The Tongkonan is never moved. One important reason for this is that a large number of placentae are buried to the east side of the house (east is associated with life in Tora'a mythology). The placentae, buried by the fathers of new-born children, are believed to call them back if in their adult life they ever journey a long way from home, so ensuring that they will always return to their house of origin.

As in so many places in modern Indonesia, the traditional house, with its cramped, dark, smoky interior, has lost its attraction for many Torala (although it still commands great ritual prestige). Many have opted for a ground-built, concrete, single-storey house in the contemporary Pan-Indonesian style, and some have adopted a wooden, pile-built Bu 's-type dwelling. Others who are more inclined towards tradition may add an extra storey and a saddleback roof; this provides more living space and room for furniture whilst retaining something of the prestige the Tongkonan affords its owner.

Flores Tourist Object

LABUANBAJO

A little town inhabited by fishermen, lies at the extreme western part of Flores Island. The town serves as a jumping off point for the trip to Komodo Island. It is a beautiful area for water skiing, wind surfing, fishing and many other marine activities.

Batu Cermin Cave is five kilometers from the town of Labuanbajo. It can be reached partly by car, and partly on foot. The grotto is 75 by 75 meters large, and contains stalactites and stalagmites. Some tunnels are narrow and dark but in others sunlight falls.

Mbeliling Conservation area: Mbeliling is one of Flores nature conservation area, here life some of Flores endemic birds ie: Flores Hanging-parrot Loriculus flosculus and Flores Crow Corvus florensis, and many other birds, nature pure and rain forest

Lake Sano Nggoang:

Located approximately 35 km east of Labuan Bajo, Thought to be one of the deepest volcanic crater lakes in the world, with recorded depths of 500 meter. Its waters are sulfuric and fed by numerous hot springs . Surroundings: Rural. Agricultural society. Traditional villages, rich in local culture.

Tado Community Eco-tourism: Tado is located approximately 45 km east of Labuan Bajo .Two closely –connected traditional West Manggarai villages, rich in local culture and traditions. Community-based ecotourism villages.

Wae Rebo Traditional Village:

the Authentic Housing of Manggarai, located about 1000m above sea level , in the middle of mountain. All are traditional houses, with really high roofs and they are on 5 levels - the top four are mainly used for storage and all the living areas are on the bottom. We will stay in a house with 8 families. Here you have chance to keep in touch with the people and learnt by seeing, asking, and feeling their culture, life and activities.

R U T E NG

Ruteng is the capital of Manggarai Regency that was once ruled by the kings of Bima. The influences of Bima. The influences of Bima and Goa are evident in prevailing titles, such as Karaeng, and in the manner of dress. The shape of the roofs with the buffalo horn symbol, may be an element inherited from the Minangkabau. The cool town of Ruteng lies at the foot of a mountain. It can be reached by air from Kupang or Denpasar via Bima, or by ferry from Bima via Labuanbajo, or from eastern part via Ende and Bajawa. Beside the fame Komodo lizards, the area has many attractions to offer the tourists, such as the caci dance, a wildlife reserve, and archeological caves

.

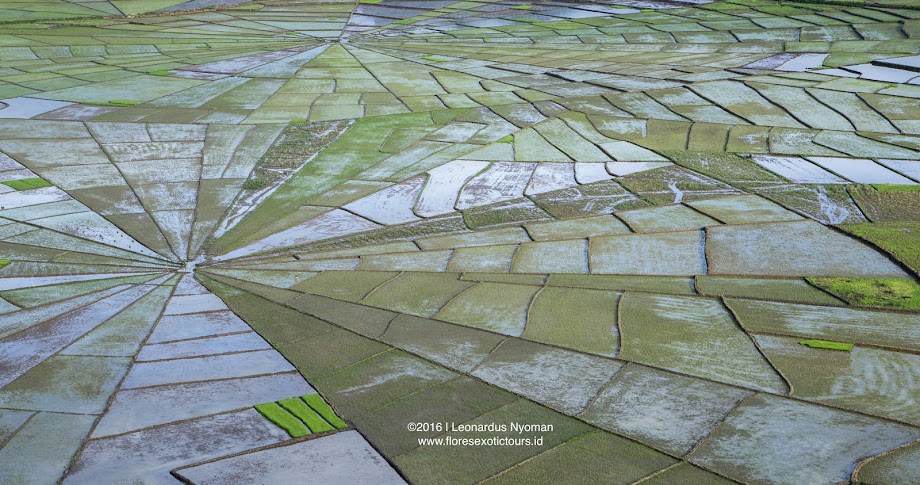

Cancar ;Golo Cara; the unique lingko rice fields, circular terraces arranged like a spider web.

Liang Bua: the place where Homo Floresiensis was founded by the archeopathology of new England university of Australia and from Indonesia. The tiny skeleton called Hobbit was discovered during a three-month excavation inside Liang Bua, Scientists believe it may represent a new human species, Homo floresiensis, The species existed alongside modern humans as recently as 13,000 years ago, yet may descend from Homo erectus, which arose some two million years ago.

BAJAWA

The capital of Ngada is Bajawa, which lies in the middle of the cool highlands. It is a pleasant little town such as is seldom found elsewhere in Flores. About 135 kilometers from Ruteng all about 5 to 7 hour - driving distance by car, Bajawa can also be reahed from Kupang by air-craft, and from Ende by car.

Abulobo and Inerie are between mountains with sharp peaks known locally as the "sky pillars", and popular among mountaineers. They are located near coast and have wonderful scenery.

B E N A

Bena is prototype of an ancient Ngada village. Such villages are found in rather great numbers in the area and can be reached by car from bajawa in about one and half hours. The way of life of the people is unique, and so are the houses and the traditional ceremonies.

R I U N G

Riung is now wellknown for its seventeen isles that makes the sea surrounding a paradise for marine lovers. Here one can dive, snorkel, and swim.

The beach is a sea-side resort with clear and calm water. There is a beautiful coral reef just off the shore.

ENDE

Ende was the site of a kingdom that existed around the end of the 1 8th century. The name today refers to the capital of the Ende regency, which includes the two autonomous territories of Lio and Ende. The people of the area therefore known as Lio Ende people. This town has for many decades been a center of government trade, education and political activity. Rebellion against the Dutch, led by a certain Nipa Do - known as the Wars of Watu Api and Mari Longa - decurred here in 1916 - 1917. And in 1934, the traditionalist leader Soekarno, who was later to become Indonesia's first president, was exiled to Ende by the Dutch colonial government.

The town Ende lies at the foot of mountains lye, lpi, Meja and Wongge. The beautiful bays of Ende, lpi, and Mbuu are favorite sites for beach-site recreation. Ende can be reached by aircraft from Kupang. And also from Denpasar via Bima, or by from Surabaya or Kupang.

The Bung Karno Museum is the old house occupied by Soekarno during his years of exile in Ende. Most of for the old furnishings are still there.

While in exile in Ende, Soekarno wrote and staged few plays, together with the Tonel Kelimutu theatre troupe. Among those plays were Rendorua Ola Nggera Nusa (Rendo That Stirred the Archipelago) and Doctor Satan, a revision on the story of Dr. Frankenstein.

Near the football field in Ende stands an old, big breadfruit tree. Under it, Soekarno often sat, working on political ideas to lead Indonesia towards independence. Those reflections presumably contributed to the opening of the Pancasila concept, which is now the state philosophy of the Indonesian Republic. Just from here was the Pancasila idea born. Today, the Pancasila Birth Monument stand on this precise spot.

KELIMUTU

East Nusa Tenggara's natural wonder and one of Indonesia's most mysterious and dramatic sights that can be found on top this mountain, some 66 kilometers from Ende, or 83 kilometers from Maumere. It has a unique and spectacular view on its three crater lakes with their respective colors. The colors, however, have changed continually since the eruption of Mount /ye in Ende in 1969.

The mountain is located at the back of Mount Kelibara, in the Wolowaru District in the Ende, Regency of Central Flores. Keli means mountain and Mutu means boiling. In short, it means volcano. To the local people, this mountain is holy, and a token of God's blessings. It provides fertility to the surrounding lands. It is both heaven and the hell to the people of Lio Ende. Many travelers and scientists, have written about Kelimutu since it was discovered by Van Suchtelen, a Ducth government officer,

in 1915

Father Bouman published an article in 1929, which made the name Kelimutu known all over the world. Since then, many researchers and tourits have come, as well as the Governor General of Batavia (Jakarta). To get to the lakes, one follows the road, from Moni, then proceed to the crater's top. Near the crater rim was a bungalow, which has now been dismantled.

The presence of the white men, or Ata Bara, was regarded disturbing to the peace of the ancestral spirits. As a result the spirits of Kelimutu disappeared. Earth quakes began rocking the land. Smoke is often released from the crater.

The eruption of 1928 caused many victims and much damage. In 1938 there was another eruption, coming from Tiwu Ata Koo Fai Noo, Ata Nuwa Muri (the Lake of Youth). The biggest took place in 1968, in which the water in the lakes was shot 10 kilometers high into the sky. The peak of Kelimutu itself is 1,690 meters high, and its lake crater I ,410. Other geological data are as follows: Tiwu Ata Polo (the Lake of Evil) has a slopping wall, 150 meters high. The lake is 380 by 280 meters large and 64 meters deep. The volume of the water is about 446,000 cubic meters.

Tiwu Ata Koo Fai Noo and Ata Nawa Muri (the Lake of Youth) has walls 128 meters high. The lake is 430 by 300 square large and 127 meters deep with a water content of about 500.000 cubic meters.

Timu Ata Bupo (the Lake of the old) has twi layers of walls, 240 meters high. The lake covers a surface of 300 by 280 meters high. The water is 67 meters deep and 345,000 cubic meters in volume. The total water content of the three lakes amounts to 1,3 million cubic meters.

In the last three ti five years, the lakes of Kelimutu have changed in color, a phenomenon caused by the geological and chemical processes in the bottom and walls of take lakes. It could also have resulted from changes in the bacteria and micro organism populations due to changes in temperature.

Another theory proposed by village elders, is that there has actually been no change at all, but that the effect is due to optical illusions. To reach Kelimutu can be done by flying to Ende or Maumere, then going by car to Kelimutu

The surrounding villages are good places serving as bases for visits to Kelimutu, particularly those who wish to have a more leisurely pace and enjoy the views along the road between Ende and maumere, or spend more time in Kelimutu. Those title villages are also known for their excellent weaving all hand made, still use natural dyes.

MAUMERE

A port town on the northeastern coast of Flores and stopover on the way to Ende or to Denpasar, and Ujungpandang, and noted for its good beaches. The bay of Maumere, Waiara, is considered the best diving spot (Flores Marine Resort) as it promise extremely rich marine life.

The resort is a paradise for all divers, underwater photographers, and for everyone interested in marone biology.

It has a beautiful sea garden filled with corals and fish. So does Koka, nearby. Accommodation and facilities for recreation are available.

Ledalero Museum at the outskirts of Maumere has an interesting collection of ethnological objects for the region. Visitors are welcome but advanced arrangements should be made. Ledalero is also a name of a major Catholic Seminary from many of Florinese priest originated.

A little town inhabited by fishermen, lies at the extreme western part of Flores Island. The town serves as a jumping off point for the trip to Komodo Island. It is a beautiful area for water skiing, wind surfing, fishing and many other marine activities.

Batu Cermin Cave is five kilometers from the town of Labuanbajo. It can be reached partly by car, and partly on foot. The grotto is 75 by 75 meters large, and contains stalactites and stalagmites. Some tunnels are narrow and dark but in others sunlight falls.

Mbeliling Conservation area: Mbeliling is one of Flores nature conservation area, here life some of Flores endemic birds ie: Flores Hanging-parrot Loriculus flosculus and Flores Crow Corvus florensis, and many other birds, nature pure and rain forest

Lake Sano Nggoang:

Located approximately 35 km east of Labuan Bajo, Thought to be one of the deepest volcanic crater lakes in the world, with recorded depths of 500 meter. Its waters are sulfuric and fed by numerous hot springs . Surroundings: Rural. Agricultural society. Traditional villages, rich in local culture.

Tado Community Eco-tourism: Tado is located approximately 45 km east of Labuan Bajo .Two closely –connected traditional West Manggarai villages, rich in local culture and traditions. Community-based ecotourism villages.

Wae Rebo Traditional Village:

the Authentic Housing of Manggarai, located about 1000m above sea level , in the middle of mountain. All are traditional houses, with really high roofs and they are on 5 levels - the top four are mainly used for storage and all the living areas are on the bottom. We will stay in a house with 8 families. Here you have chance to keep in touch with the people and learnt by seeing, asking, and feeling their culture, life and activities.

R U T E NG

Ruteng is the capital of Manggarai Regency that was once ruled by the kings of Bima. The influences of Bima. The influences of Bima and Goa are evident in prevailing titles, such as Karaeng, and in the manner of dress. The shape of the roofs with the buffalo horn symbol, may be an element inherited from the Minangkabau. The cool town of Ruteng lies at the foot of a mountain. It can be reached by air from Kupang or Denpasar via Bima, or by ferry from Bima via Labuanbajo, or from eastern part via Ende and Bajawa. Beside the fame Komodo lizards, the area has many attractions to offer the tourists, such as the caci dance, a wildlife reserve, and archeological caves

.

Cancar ;Golo Cara; the unique lingko rice fields, circular terraces arranged like a spider web.

Liang Bua: the place where Homo Floresiensis was founded by the archeopathology of new England university of Australia and from Indonesia. The tiny skeleton called Hobbit was discovered during a three-month excavation inside Liang Bua, Scientists believe it may represent a new human species, Homo floresiensis, The species existed alongside modern humans as recently as 13,000 years ago, yet may descend from Homo erectus, which arose some two million years ago.

BAJAWA

The capital of Ngada is Bajawa, which lies in the middle of the cool highlands. It is a pleasant little town such as is seldom found elsewhere in Flores. About 135 kilometers from Ruteng all about 5 to 7 hour - driving distance by car, Bajawa can also be reahed from Kupang by air-craft, and from Ende by car.

Abulobo and Inerie are between mountains with sharp peaks known locally as the "sky pillars", and popular among mountaineers. They are located near coast and have wonderful scenery.

B E N A

Bena is prototype of an ancient Ngada village. Such villages are found in rather great numbers in the area and can be reached by car from bajawa in about one and half hours. The way of life of the people is unique, and so are the houses and the traditional ceremonies.

R I U N G

Riung is now wellknown for its seventeen isles that makes the sea surrounding a paradise for marine lovers. Here one can dive, snorkel, and swim.

The beach is a sea-side resort with clear and calm water. There is a beautiful coral reef just off the shore.

ENDE

Ende was the site of a kingdom that existed around the end of the 1 8th century. The name today refers to the capital of the Ende regency, which includes the two autonomous territories of Lio and Ende. The people of the area therefore known as Lio Ende people. This town has for many decades been a center of government trade, education and political activity. Rebellion against the Dutch, led by a certain Nipa Do - known as the Wars of Watu Api and Mari Longa - decurred here in 1916 - 1917. And in 1934, the traditionalist leader Soekarno, who was later to become Indonesia's first president, was exiled to Ende by the Dutch colonial government.

The town Ende lies at the foot of mountains lye, lpi, Meja and Wongge. The beautiful bays of Ende, lpi, and Mbuu are favorite sites for beach-site recreation. Ende can be reached by aircraft from Kupang. And also from Denpasar via Bima, or by from Surabaya or Kupang.

The Bung Karno Museum is the old house occupied by Soekarno during his years of exile in Ende. Most of for the old furnishings are still there.

While in exile in Ende, Soekarno wrote and staged few plays, together with the Tonel Kelimutu theatre troupe. Among those plays were Rendorua Ola Nggera Nusa (Rendo That Stirred the Archipelago) and Doctor Satan, a revision on the story of Dr. Frankenstein.

Near the football field in Ende stands an old, big breadfruit tree. Under it, Soekarno often sat, working on political ideas to lead Indonesia towards independence. Those reflections presumably contributed to the opening of the Pancasila concept, which is now the state philosophy of the Indonesian Republic. Just from here was the Pancasila idea born. Today, the Pancasila Birth Monument stand on this precise spot.

KELIMUTU

East Nusa Tenggara's natural wonder and one of Indonesia's most mysterious and dramatic sights that can be found on top this mountain, some 66 kilometers from Ende, or 83 kilometers from Maumere. It has a unique and spectacular view on its three crater lakes with their respective colors. The colors, however, have changed continually since the eruption of Mount /ye in Ende in 1969.

The mountain is located at the back of Mount Kelibara, in the Wolowaru District in the Ende, Regency of Central Flores. Keli means mountain and Mutu means boiling. In short, it means volcano. To the local people, this mountain is holy, and a token of God's blessings. It provides fertility to the surrounding lands. It is both heaven and the hell to the people of Lio Ende. Many travelers and scientists, have written about Kelimutu since it was discovered by Van Suchtelen, a Ducth government officer,

in 1915

Father Bouman published an article in 1929, which made the name Kelimutu known all over the world. Since then, many researchers and tourits have come, as well as the Governor General of Batavia (Jakarta). To get to the lakes, one follows the road, from Moni, then proceed to the crater's top. Near the crater rim was a bungalow, which has now been dismantled.

The presence of the white men, or Ata Bara, was regarded disturbing to the peace of the ancestral spirits. As a result the spirits of Kelimutu disappeared. Earth quakes began rocking the land. Smoke is often released from the crater.

The eruption of 1928 caused many victims and much damage. In 1938 there was another eruption, coming from Tiwu Ata Koo Fai Noo, Ata Nuwa Muri (the Lake of Youth). The biggest took place in 1968, in which the water in the lakes was shot 10 kilometers high into the sky. The peak of Kelimutu itself is 1,690 meters high, and its lake crater I ,410. Other geological data are as follows: Tiwu Ata Polo (the Lake of Evil) has a slopping wall, 150 meters high. The lake is 380 by 280 meters large and 64 meters deep. The volume of the water is about 446,000 cubic meters.

Tiwu Ata Koo Fai Noo and Ata Nawa Muri (the Lake of Youth) has walls 128 meters high. The lake is 430 by 300 square large and 127 meters deep with a water content of about 500.000 cubic meters.

Timu Ata Bupo (the Lake of the old) has twi layers of walls, 240 meters high. The lake covers a surface of 300 by 280 meters high. The water is 67 meters deep and 345,000 cubic meters in volume. The total water content of the three lakes amounts to 1,3 million cubic meters.

In the last three ti five years, the lakes of Kelimutu have changed in color, a phenomenon caused by the geological and chemical processes in the bottom and walls of take lakes. It could also have resulted from changes in the bacteria and micro organism populations due to changes in temperature.

Another theory proposed by village elders, is that there has actually been no change at all, but that the effect is due to optical illusions. To reach Kelimutu can be done by flying to Ende or Maumere, then going by car to Kelimutu

The surrounding villages are good places serving as bases for visits to Kelimutu, particularly those who wish to have a more leisurely pace and enjoy the views along the road between Ende and maumere, or spend more time in Kelimutu. Those title villages are also known for their excellent weaving all hand made, still use natural dyes.

MAUMERE

A port town on the northeastern coast of Flores and stopover on the way to Ende or to Denpasar, and Ujungpandang, and noted for its good beaches. The bay of Maumere, Waiara, is considered the best diving spot (Flores Marine Resort) as it promise extremely rich marine life.

The resort is a paradise for all divers, underwater photographers, and for everyone interested in marone biology.

It has a beautiful sea garden filled with corals and fish. So does Koka, nearby. Accommodation and facilities for recreation are available.

Ledalero Museum at the outskirts of Maumere has an interesting collection of ethnological objects for the region. Visitors are welcome but advanced arrangements should be made. Ledalero is also a name of a major Catholic Seminary from many of Florinese priest originated.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

Seventeen island, Riung Marine park Ngada-Flores

Label:

alam,

exotic,

flores,

laut,

leonardus nyoman,

marine,

park,

photo,

pulau,

riung,

taman,

tours,

tujuh belas,

wisata

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

Wair Nokerua, a Trek to Miracle

Flores history in Catholicism has gone long with St. Francis Xavier as one of the charismatic figures. Wair Nokerua is a water spring named after him and is believed by local community to be the trace of his miracles. Wair in local language means water (derived from) he who lives celibate or pastor (nokerua).

Being one of the special interest tourist sites of Sikka District, Wair Nokerua is located on the beach of Kolisia Village, Sub District Magepanda, Sikka District. It is only ± 20km from Maumere and promises a rural nature living experience to incoming travelers. From Maumere, take the North coast Trans Flores route, turn right after ± 10m at Kolisia Village sign. You will enter an unpaved road enough for one car to pass. Crossing a river to get to the village where the beach is will be one of the most interesting parts the cross-country trek Wair Nokerua offers. Don’t forget to take your camera along because loads of beautiful village views await you.